Minor Arcana Midrash: The Blinding of Isaac and the Eight of Swords.

/No, it’s not a typo. The story of Abraham almost sacrificing his son Isaac is called the Akedah, which in Hebrew means “binding,” thus the binding of Isaac. And we’ll start with the binding, because this is where the blinding of Isaac begins.

The great medieval commentator on the Bible, Rashi, wrote that:

When Isaac was bound on the altar, and his father was about to slaughter him, the heavens opened, and the ministering angels saw and wept, and their tears fell upon Isaac’s eyes. As a result, his eyes became dim.

After the Akedah, Isaac does not return with his father to Beersheba. Commentators make much of the fact that Isaac disappears from the story as soon as the sacrifice is halted. He isn’t present for his mother’s death and burial. The first time Isaac reappears in the story is when Abraham’s servant returns from his task of finding Isaac a wife. In Genesis 24:63-64 we are told that when Isaac was walking in a field:

“he raised his eyes and saw, look, camels were coming. And Rebekah raised her eyes and saw Isaac….”

The rabbinic commentators make a lot of Isaac’s failing to see Rebekah. But the last time we saw Isaac, he was bound on an altar and looking up at his father’s knife ready to take his life. So if there were ever a reason for traumatic blindness, this would be it.

The next time his vision is mentioned, is during the famous scene where Jacob impersonates his brother Esau to steal his father’s blessing. The episode begins by noting that Isaac has grown old and his eyesight has dimmed, thus making the impersonation possible. It’s clear from the text that Isaac was suspicious, but that he gave the blessing to Jacob anyway.

This not age related vision loss—it is a blindness born of family trauma, so that Isaac isn’t able to clearly see people, or completely trust them.

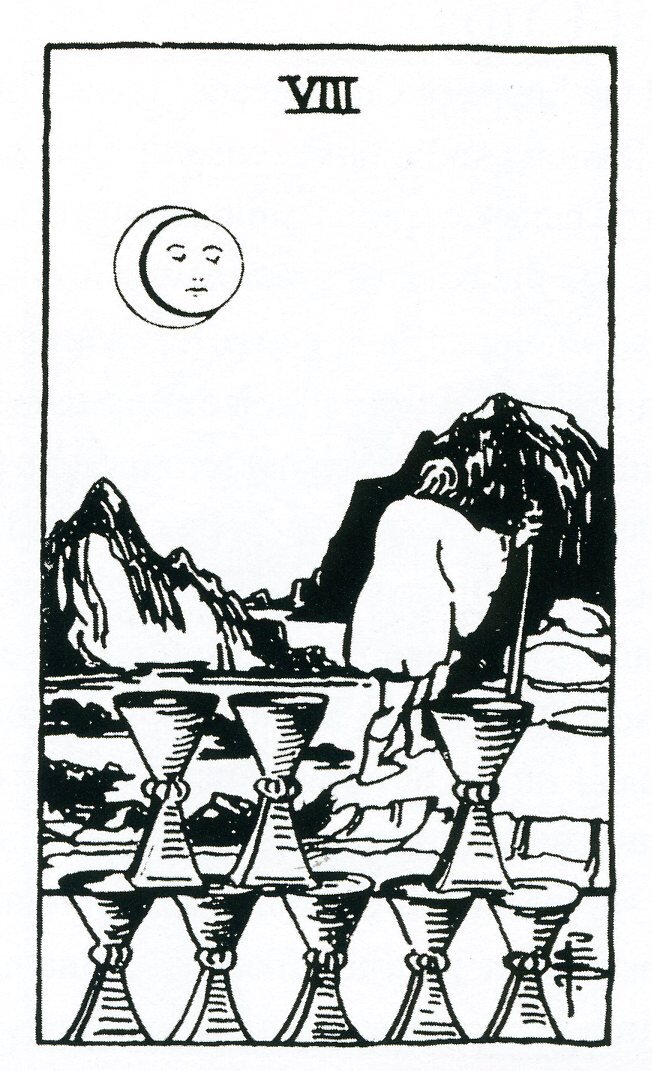

So let’s turn to the Eight of Swords, and another binding and blinding. In the image in the Waite-Smith deck we see a woman bound with a cloth of some kind that not only restricts her movement, but also covers her eyes. If she were to take a step, on ground that looks muddy, she’d be certain to fall and cut herself on the swords arrayed around her.

The suit of swords can represent the world of the mind, thoughts, ideas. So one way we could look at the meaning of this card is as someone who is blinded and bound by their preconceptions, so that they can’t really see what’s in front of them. This is hinted at by the rather loose binding of the cloth. It’s as though with just a little wriggle, the fabric would fall to her feet, she could lift the blindfold from her eyes (not unlike the couple enslaved by the Devil, who could remove the loose chains that only appear to hold them) and walk away free.

The Eight of Swords is the Sefira of Hod, Humility, in Yetzirah. It’s a coded teaching that our personal and family history, our culture and traditions can bind and blind us from seeing truth. And that rather than identify with these ideas, if we are to be free, we must see these ideas for the limitations they are and let go of them.

In Genesis, Isaac blindly repeats the mistakes of his father, from trying to pass off Rebekah as his sister to save his life and by fomenting discord in his family by actively preferring one son over the other. We all repeat the mistakes of our parents in one way or another. And we all inherit their ideas, preconceptions and prejudices. But if we are ever to experience liberating insight, it must begin with liberating ourselves from the short-sightedness of familial and cultural prejudice and by clearly seeing and healing family trauma.

Lessons we can learn both from the story of Isaac’s blindness and the Eight of Swords.